Film Review - Strangers on a Train

We have all had someone in our lives that we have wanted ‘disposed of’, right? Nearly every human being has experienced a moment in which their emotions have overrun their sense reason and logic and, in a fit of anger, claim that they want to ‘strangle’ or kill someone who has caused them some form of pain or anguish. It’s no big secret. But what if the opportunity to do just that and get away with it scot-free presented itself to you? Would you take it? That’s the idea behind Alfred Hitchcock’s rather sadistic (in a good way) drama Strangers on a Train. Celebrity tennis player Guy Haines and Bruno Anthony meet on a train coincidently, or so it would seem. Bruno, recognizing Guy, strikes up a conversion in which Guy reveals that he wants a divorce from his backstabbing wife, Miriam, so he can marry Anne Morton, the daughter of a respectable U.S. Senator. Over lunch Bruno confesses to Guy that he too wants a nuisance removed from his life, his over controlling step-father. He then suggests a perfect plan to remove the obstacles of each other’s lives barring their way from living a happy life. His scheme is that the two of them ‘exchange murders’, committing the murder of the other person so that person closest to the victim has an airtight alibi and the actual murderer can not be accused of the crime because he and the victim are complete strangers.

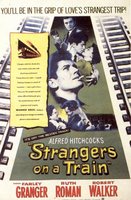

We have all had someone in our lives that we have wanted ‘disposed of’, right? Nearly every human being has experienced a moment in which their emotions have overrun their sense reason and logic and, in a fit of anger, claim that they want to ‘strangle’ or kill someone who has caused them some form of pain or anguish. It’s no big secret. But what if the opportunity to do just that and get away with it scot-free presented itself to you? Would you take it? That’s the idea behind Alfred Hitchcock’s rather sadistic (in a good way) drama Strangers on a Train. Celebrity tennis player Guy Haines and Bruno Anthony meet on a train coincidently, or so it would seem. Bruno, recognizing Guy, strikes up a conversion in which Guy reveals that he wants a divorce from his backstabbing wife, Miriam, so he can marry Anne Morton, the daughter of a respectable U.S. Senator. Over lunch Bruno confesses to Guy that he too wants a nuisance removed from his life, his over controlling step-father. He then suggests a perfect plan to remove the obstacles of each other’s lives barring their way from living a happy life. His scheme is that the two of them ‘exchange murders’, committing the murder of the other person so that person closest to the victim has an airtight alibi and the actual murderer can not be accused of the crime because he and the victim are complete strangers.Seems simple enough, right? That is what Bruno thinks as well but it is this precise arrogance which will inexplicably lead to his downfall. Guy, upon hearing the devious proposal, jollies Bruno along and after leaving the train tries to put the whole affair behind him. Only he can’t, at least not for long. It appears as though Bruno was quite serious about his proposal, presenting Guy when he returns to his home in Baltimore with the eyeglasses of his dead wife Miriam. Guy however is extremely reluctant to follow through with his end of the bargain when he never committed to the plan in the first place, at least not seriously. And even if he were willing to do so, he wouldn’t be able to, not with the police watching him like a hawk. The police have privately named Guy as a prime suspect because of his public altercation with Miriam the day of the murder (with numerous eyewitnesses), his admittance to Anne that he wanted to ‘strangle’ Miriam, and no alibi for his exact whereabouts at the time of the murder (he does have a witness who was with him on the train to Baltimore at the time of the murder but unfortunately for Guy he was quite intoxicated and couldn’t remember him the next day). What follows is a series of events in which Bruno, coming to the conclusion that Guy will not fulfill his end of the bargain, tries to frame Guy for the murder of his wife (turning his cigarette lighter which was almost left at the scene of the crime over to the police, thus incriminating him) and Guy fighting to restore his good name while at the same time keeping the police who are tailing his every move off his trail.

In the conventional vein of Shadow of a Doubt, Hitchcock uses doubles or pairs in Strangers on a Train to figure in the balance of good and evil. The pairing of Guy Haines, the dashing all-American youth, and Bruno Anthony, the obsessive and malevolent outsider, is Hitchcock most glaring example of this recurrent theme. Two seemingly distinct personalities yet at the same time each complimentary to one another. Other pairs include the two drinks Bruno orders on the train during lunch, the two crisscrossing tennis rackets on Guy’s cigarette lighter, the double-vision of Miriam’s death through her eyeglasses, the startling resemblance Barbara Morton shares with Miriam, and, most discreetly, the words ‘two imposters’ (from the Rudyard Kipling poem ‘If’) on a beam above Guy’s head as he leaves the last tennis match of the film.

There are at least five scenes in particular found in this film in which the true cinematic genius of Alfred Hitchcock and his creative dramatic vision shines through brilliantly onto the screen. The first is the sequence in which Bruno follows Guy’s wife, Miriam, and her two ‘boyfriends’ into the Tunnel of Love. His shadow is projected onto the wall and from the viewpoint of the audience it appears as though he is overtaking them. A scream from Miriam, which later reveals to be out of excitement and pleasure, not terror and death, while the two boats are still inside the tunnel creates an image in our minds of what may be taking place. Instead it is a foreshadowing of what is yet to come.

The second scene takes place immediately after the Tunnel of Love sequence when the actual murder of Miriam occurs. Miriam and her two ‘boyfriends’ have just exited their boat in a secluded area not far off from the fair grounds when in their excitement they become separated. Bruno comes up from behind Miriam and asks if she who he believes her to be. He then grabs her neck and proceeds to strangle her to death, leaving her barely able to let out even a whisper in her pleas for help. Though Hitchcock does not show the actual murder directly, he goes one step further, from an artistic standpoint that is. He shows the strangulation of Miriam through her eyeglasses which have fallen to the ground. These eyeglasses are of particular importance as they will reappear on the face of another character (similar but not the exact same glasses as Miriam’s) later on in the film. This in turn will cause Bruno to flashback to the night of the murder and pass out.

The third is easily the most recognizable. In this scene Guy as he prepares for his tennis match pans the crowd of spectators sitting in the grandstands observing the tennis match in front of them, each one with his or her head swiveling back and forth as each volley is shot across the court. All, that is, with the exception of one, Bruno Anthony, whose gaze is set unwavering on Guy. This hair-raising moment demonstrates the merciless persistence of Bruno.

The fourth takes place in the midst of yet another tennis match, this one involving Guy who must win in three sets if he wishes to beat Bruno back to his hometown and retrieve his cigarette lighter before Bruno has the chance to plant it at the scene of Miriam’s murder and frame him for the crime. He must compete in the match and go on with his usual lifestyle to avoid further suspicion on the part of the police. Bruno arrives in Guy’s hometown aboard a train just as Guy’s tennis match is taking place. Suddenly, as he is pretentiously tosses it slightly in his right hand, Guy’s cigarette lighter, the solitary advantage he holds over Guy’s head, drops directly into a sewer drain. The tension of Guy’s pivotal tennis match and Bruno’s insufferable struggle to reach the cigarette lighter just barely out of his grasp adds further vigor to the film. Two different yet at the same time congruent personalities, both in actions and words.

And then of course there is the merry-go-round sequence, Hitchcock’s crescendo for Strangers on a Train. Here the operator of the classic carnival favorite is accidentally shot in the head by a police officer who is in hot pursuit of Guy Haines who races across the fair grounds having just spotted Bruno Anthony. The dead man’s last act is to pull on the lever controlling the amusement park ride causing it to careen out of control (to the delight of a five-year old boy who believes this to be part of the thrill of the ride). A carnival worker crawls on his belly under the gyrating carousel, reaches the control switch, and pulls it back which then causes the ride to short-circuit and collapse on the ground below. The scene itself is technologically marvelous, especially given the time period in which it was shot.

Guy escapes relatively unscathed. Bruno on the other hand is not so lucky. His body is pinned under the weight of a carousel horse and other debris. Guy pleads with Bruno in his last breathes to fess up and reveal who really strangled Miriam, but he refuses, resolute to the bitter end. However, even in death his bitter arrogance does him in, his right hand clutching Guy’s cigarette lighter. As soon as the police realize Bruno has Guy’s cigarette lighter, they clear him of murder charges against his wife.

While Patricia Highsmith, the lesbian author of the Tom Ripley book series, deserves credit for the basis for Strangers on the Train, true credit lies with Czenzi Ormonde who broke dramatically from the source material to fit the inspirational vision of director Alfred Hitchcock. It’s not perfect, by any means, and certainly far from the director’s best work, though arguably within the top ten of films made while he was in the United States. Strangers on a Train remains an engaging, first-rate thriller even by today’s standards.

My Rating: **** ½ out of 5 (Grade: A-)

<< Home