Film Review - Rope

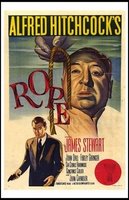

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, the first of what would eventually become four collaborative efforts with actor and close friend James Stewart, was based not only on a popular British play, Rope’s End (the re-titling given to the play when it came to Broadway after the release of the 1948 Hitchcock picture) by Patrick Hamilton, but an actual event as well. Hitchcock much like Hume Cronyn and Henry Traver’s characters in Shadow of a Doubt was quite the aficionado when it came to famous murder cases, using many he followed as a child in England as inspiration for some of his early works. It is no surprise then to see why Rope peeked his interest. Hamilton’s play was based on the murder trial of Nathan Freudenthal Leopold, Jr. and Richard A. Loeb, more commonly referred to as simply Leopold and Loeb, two wealthy and homosexual University of Chicago students who inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s theory of advanced ‘supermen’ sought to commit the perfect murder. Their victim, fourteen-year old Bobby Franks, was bludgeoned with a chisel, suffocated to death, burned with acid so as to make identification all the more difficult, and dumped in a sewage pipe. Avoiding a jury trial, the two ‘men’ were given ninety-nine years to life, though neither one served their full sentence (Loeb was killed in prison at age thirty-five and Leopold was paroled in 1958 and moved to Puerto Rico).

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, the first of what would eventually become four collaborative efforts with actor and close friend James Stewart, was based not only on a popular British play, Rope’s End (the re-titling given to the play when it came to Broadway after the release of the 1948 Hitchcock picture) by Patrick Hamilton, but an actual event as well. Hitchcock much like Hume Cronyn and Henry Traver’s characters in Shadow of a Doubt was quite the aficionado when it came to famous murder cases, using many he followed as a child in England as inspiration for some of his early works. It is no surprise then to see why Rope peeked his interest. Hamilton’s play was based on the murder trial of Nathan Freudenthal Leopold, Jr. and Richard A. Loeb, more commonly referred to as simply Leopold and Loeb, two wealthy and homosexual University of Chicago students who inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s theory of advanced ‘supermen’ sought to commit the perfect murder. Their victim, fourteen-year old Bobby Franks, was bludgeoned with a chisel, suffocated to death, burned with acid so as to make identification all the more difficult, and dumped in a sewage pipe. Avoiding a jury trial, the two ‘men’ were given ninety-nine years to life, though neither one served their full sentence (Loeb was killed in prison at age thirty-five and Leopold was paroled in 1958 and moved to Puerto Rico).James Stewart was drafted into the United States Army Air Corps one year prior to the United States’ official entry into World War II, serving admirably in combat and rising to the rank of colonel. However, upon his return from war in the mid-1940s, he became increasingly disillusioned with Hollywood and was on the verge of quitting the movie business altogether. Stewart took up Hitchcock’s offer to play Rupert Cadell in his feature film adaptation of Rope if he was allowed to wave his salary for a percentage of the film’s box office gross. It was accepted.

Rope is a very short film, even by today’s standards, clocking in at one hour and twenty-five minutes. Therefore everything rides on the performances of the three main leads and Stewart for one does so with gusto. In the Patrick Hamilton play, Rupert in addition to being the boys’ former schoolmaster was also their one-time gay lover. It however makes more sense for Rupert to be played off as Brandon and Phillip’s surrogate father then their lover because as a surrogate father he must bear witness to the sadistic manipulation of his ideas and face the difficult task of admit to his own ‘sons’ that he was wrong in what he said. It is even more painful therefore for him to have to turn his ‘children’ into the authorities for something he taught them but never believed they would ever seriously consider. The final scene in which Stewart wrestles with himself over the gun is sheer brilliance. Does he shoot the gun out the window and alert the police, take justice into his own hands and kill the murderers himself, or in a fit of disparity turn the gun on himself? Chilling and intriguing to the bitter end, Stewart’s convincing performance truly makes this film the classic that it is.

John Dall is downright nefarious as Brandon Shaw, the ‘mastermind’ if you will behind this experimentation in Nietzsche’s ‘superman’ theory and how such men are above the moral limitations of their inferiors. It is to say the least a bit unnerving to see a sense of accomplishment, even distinct pleasure, come across his face after strangling young David to death and then proceeding to host a social get-together with the father and girlfriend of the victim in the same room as the trunk containing the victim’s corpse. Dall uses witty yet dry, dark humor throughout the film, a brutal honesty which is seriously unwarranted in areas, such as immediately following David’s death, but this rightfully falls in line with his character. This is a man whose obsession with playing God alienates everyone’s feelings but his own. His arrogance, his avid fixation on proving not to his former headmaster but to himself that he can get away with murder, proves to be his downfall.

Phillip Morgan, played eloquently by then-relatively unknown Farley Granger, is the precise opposite of Brandon Shaw in every way. While he does partake in the experiment of killing David Kentley just for the thrill of getting away with it, he’s dragged into more by Brandon and feels less of a desire or need to flaunt it in everyone’s faces. He just wants to dispose of the body and be done with it once and for all. This of course would be the smart way to do it. Whether because of a lack of courage or his unwillingness to upset his ‘relationship’ with Brandon, he doesn’t. This adds further tension to his already guilt racked conscience, something Brandon sincerely lacks, leading him to take up heavy drinking and chain smoking to ease his troubled mind. Sadly these serve as tell-tale signs for a genius like Rupert to pick up on that something is amiss.

While seen only for the first few brief seconds of the picture after the opening credits, his presence is felt nonetheless throughout the entire film. Similar to how Janet Leigh’s early demise in Psycho two decades later reverberated throughout the story, so does Hogan’s, though certainly less memorably. The presence of his ‘coffin’ in the middle of the room amidst the social get-together mirrors Edgar Allen Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart for Phillip with the reemergence of the murder weapon, the rope with which David was strangled to death, adding only further burden to his guilt.

To this day Rope remains one of director Alfred Hitchcock’s most enduring and innovative motion picture drama. It stands as his first film to be filmed entirely in Technicolor. Although he would on occasion revert back to black-and-white in cases of budgetary constraints, Psycho the most likely famous example of this, as well as his nostalgia for artistic value, it showed once more he could adapt his art with the changing times as easily or better then anyone else in the field. With the exception of the opening credits, Rope is shot on one solitary set located within a soundstage, much as though you were watching a play performed on stage in front of you. Regardless of the confined space the performances occupy, the atmospheric tension is nothing short of electrifying all the way to the very end. In addition, Hitchcock creates the illusion, with some success, of one continuous shot. In reality, however, the one-hundred and eight minute motion picture was broken down into ten segments each ranging in length from four ½ minutes to just over ten minutes. It is rather obvious to audiences today that whenever a performer or a piece of furniture is moved in way of the camera so that it covers up the entire screen that it is Hitchcock’s way of covering up splits in the film segments. Nonetheless, it proved at least a reasonably effective film technique that he used once more in filming Under Capricorn for Transatlantic Pictures.

It is hard, then as it is today, not to pick up on the homosexual overtones of Rope. The closeness and quasi-intimacy Brandon and Phillip share together especially early on after they have killed David and stuffed his body inside the trunk suggest they are sharing a sexual liaison with one another. Brandon however can be viewed more as bi-sexual in nature as dialogue from him suggests that he had a short-lived relationship with David’s current girlfriend and soon to be fiancée, Janet Walker. In an ironic bit of taste, director Alfred Hitchcock cast John Dall and Farley Granger, both homosexuals, to play the roles of two gay students. Original choices were Cary Grant, long rumored to be bi-sexual, as Rupert and Montgomery Clift who after accepting the role backed out of the picture out of fear of being exposed as a homosexual. It is unknown whether James Stewart who replaced Grant as Rupert knew of the homoerotic overtones of his character or the film in general. However, any suggestion that Rupert is a homosexual is lost in Stewart’s performance. In addition, screenwriter Arthur Laurents was gay and in his published memoirs admitted to having a sexual relationship with actor Farley Granger. Much of the homoerotic dialogue and choreography of Patrick Hamilton’s original play were cut from the final print of the film but Hitchcock however was able to keep the suggestion in the minds of audiences with the memories of Leopold and Loeb still fresh in their minds.

My Rating: **** ½ out of 5 (Grade: A)

<< Home