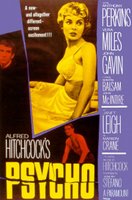

Film Review - Psycho

Today Psycho stands as a testament to the artistic genius of director Alfred Hitchcock. As simple as Joseph Stefano’s screenplay may be, it has risen over the decades to become the quintessential horror film of all time. Few, if any, have matched it, even the ‘shot-by-shot’ remake in 1998. But as horrifying as Alfred Hitchcock’s psychological thriller is, Psycho, sadly, has some basis in fact. Robert Bloch’s novel, the primary source of the film, based the character of Norman Bates (with the exception of his physical stature) on Edward Gein, one of this country’s most notorious murderers. While investigating the disappearance of a convenience store clerk named Bernice Worden, police upon entering Gein’s residence were shocked to discover not only Bernice’s body decapitated, hung upside down by her ankles, and slit up-and-down the middle like a deer but skullcaps used as soup bowls, a necklace of human lips, a belt made of nipples, a human heart in a saucepan, dead-skin masks, and lampshades and an entire wardrobe fabricated from human skin. Gein’s murderous rampage (this is a topic of some dispute – while Gein could only be linked directly with the deaths of two people, at least six people were reported missing from the towns of Plainsville and La Crosse, Wisconsin, between 1947 and 1957) in the small Midwestern town of Plainsville, Wisconsin, inspired not only Robert Block’s gripping suspense novel and the now-famous Alfred Hitchcock horror picture which followed but also Deranged, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (and all its subsequent sequels and remakes), and Thomas Harris’s novel, The Silence of the Lambs, which in turn inspired the Academy Award-winning motion picture of the same name, starring Anthony Hopkins and Jodi Foster.

Today Psycho stands as a testament to the artistic genius of director Alfred Hitchcock. As simple as Joseph Stefano’s screenplay may be, it has risen over the decades to become the quintessential horror film of all time. Few, if any, have matched it, even the ‘shot-by-shot’ remake in 1998. But as horrifying as Alfred Hitchcock’s psychological thriller is, Psycho, sadly, has some basis in fact. Robert Bloch’s novel, the primary source of the film, based the character of Norman Bates (with the exception of his physical stature) on Edward Gein, one of this country’s most notorious murderers. While investigating the disappearance of a convenience store clerk named Bernice Worden, police upon entering Gein’s residence were shocked to discover not only Bernice’s body decapitated, hung upside down by her ankles, and slit up-and-down the middle like a deer but skullcaps used as soup bowls, a necklace of human lips, a belt made of nipples, a human heart in a saucepan, dead-skin masks, and lampshades and an entire wardrobe fabricated from human skin. Gein’s murderous rampage (this is a topic of some dispute – while Gein could only be linked directly with the deaths of two people, at least six people were reported missing from the towns of Plainsville and La Crosse, Wisconsin, between 1947 and 1957) in the small Midwestern town of Plainsville, Wisconsin, inspired not only Robert Block’s gripping suspense novel and the now-famous Alfred Hitchcock horror picture which followed but also Deranged, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (and all its subsequent sequels and remakes), and Thomas Harris’s novel, The Silence of the Lambs, which in turn inspired the Academy Award-winning motion picture of the same name, starring Anthony Hopkins and Jodi Foster.Film veteran Saul Bass produces yet another powerful title sequence (this time, gray horizontal lines moving back and forth across the screen, imitating the slashing motions of the psychotic killer soon to follow) accompanied by what is easily Bernard Herrmann’s most recognizable musical score. Rather then a typical ‘blow-by-blow’ account of the film, specific points of detail which enhance the motion picture experience of Psycho should be pointed out to audiences. They then can discover the rest on their own.

In a clever symbolic nod by director Alfred Hitchcock, Marion’s underwear and bra change from pure white which she was wearing after having an afternoon tryst with her boyfriend Sam to pitch black after she takes the forty-thousand dollars back to her apartment instead of the bank like her boss instructed. Signifying her descent into darkness, Marion intends on running away with the money to California and use it to live ‘happily ever after’ with Sam, free from their financial woes.

Marion’s shower is a baptismal-like cleansing of her soul. She is prepared to return to Phoenix, Arizona and face the consequences of her actions, in this case stealing the forty-thousand dollars, but not before she has a chance to ‘wash her sins away’. With this simple act she will have returned home with a clear conscience. It is therefore even more shocking when Marion is brutally stabbed to death in the shower moments later. She steps into the shower, turns on the warm water, and absorbs herself in her own ‘private island’ where her cares simply melt away, oblivious of the fate that is about to befall her. As Marion proceeds with her shower, a faint shadow in the background can be seen through the shower curtain moving toward us inside the shower itself where Marion is right now. The shower curtain is then pushed violently aside, piercing violins screeching as a mysterious figure (only her bun-like gray hair and flower dress appear visible) stabs at the audience with what appears to be a butcher knife. Only after audience members have screamed first, Marion turns around and screams a close-up of her wide-open mouth shown. Nothing is explicitly seen (whether censors wouldn’t permit it or this was Hitchcock’s intention all along is unclear) but our own imagination fills in the gaps of this forty-five second sequence with images of a violent rape, making this all the more excruciating. The figure then leaves. Marion, mortally wounded, falls back, slowly inching her way down the wall of the shower, her arm fully stretched as if pleading with her last breath for help from the audience. She grabs the shower curtain and tares it down, limping over as blood slowly flows down the drain symbolizing the end of her life. She is free of her cares but she is also dead so she is not able to enjoy her liberation. The close-up of the drain dissolves into Marion’s transfixed eye, lifelessly starring back at us as if to haunt us, though there was clearly nothing we could have done to stop it. This is all the more an example of cruel irony since earlier a police officer advised her that she would have been safer in a motel then sleeping in her car on the side of the roadway. Shows what he knows.

The eerie silence shortly after Marion’s death is shattered by Norman cries from the house. “Mother! Oh, God! Mother!” he shouts, “Blood! Blood!” He runs down the hill and into Marion’s motel room only to discover her lifeless body slumped over the side of the bathtub. He quickly turns and covers his mouth, either in shock or in efforts to stifle a scream. Once he regains his composure, he sets about covering up the crime scene – moping up the blood, turning off the water, wrapping Marion’s corpse in the shower curtain and then dumping it along with all her possessions into the trunk of her car. Normally the audience would frown upon such an action but at this point we still want to believe ‘mother’ was behind Marion’s death, not Norman, which makes his protection of his fragile mother all the more sympathetic in our eyes. If you’ll notice closely, Marion’s license plate reads ‘NFB 418’ which stands for Norman Francis (patron saint of birds) Bates. Norman then drives the car to a swamp near the motel, steps out, and proceeds to push the vehicle into the quicksand, all the while nervously scanning for any sign of witnesses. Both he and the audience who at this point are on his side breathe a collective sigh of relief when the last flitting images of the car sink beneath the swamp.

A detective (likely hired by Cassidy) investigating the disappearance of Marion Crane eventually winds up at the shady Bates Motel off the old highway. As he pulls in, Norman is standing in the doorway of the motel office eating candy from a small paper bag. He’s just about to change the linens on all the cabin beds even though, he claims, no one has slept in them for some time. He does so out of habit because he finds the smell of dampness ‘creepy’. Taken into the motel office, Arbogast begins to interrogate Bates about Marion’s disappearance. Bates of course denies seeing the girl. Arbogast’s choice of words to try and convince Bates to at least examine a photograph of her before responding is of course ironic. “Would you mind looking at the picture before ‘committing’ yourself,” he asks. Norman’s handing over of the guest registry leaves him cornered. Arbogast discovers the name ‘Marie Samuels’, an alias for Marion Crane which proves she stayed at the Bates Motel recently. The interrogation scene between the detective and Norman Bates is classic. Watch closely as Norman’s mannerisms become increasingly erratic, causing him to stutter and stammer substantially. As he is about to leave, Arbogast notices a light on in the house behind the Bates Motel. He asks Norman if he lived with anyone. He at first denies living with anyone but then when he admits he lives with his mother. His excuse for lying before was because his mother’s ‘condition’ makes it as though he is living alone. Norman however indicts himself even further when, responding to Arbogast’s accusation that he might have been ‘fooled’ by Marion into having him hide her, possibly for sex, he says, “Let's put it this way. She might have fooled me, but she didn't fool my mother”. And when Bates refuses to allow the detective to question the mother and advises him to leave, Arbogast’s suspicions are raised even further.

It isn’t long before Arbogast returns to the Bates Motel and, having searched the motel office for any sign of Norman, sneaks his way up to the house above the motel, all the while Norman is lingering in the shadows. Arbogast slowly climbs the stairs leading to mother’s room. What follows is one of the most brilliant and frightening scenes in the film. Violins screech as an overhead shot shows ‘mother’ slashing the detective’s face. Arbogast falls backward down the stairs, landing on his back at the bottom. ‘Mother’ quickly pursues him and makes several deep stabs into his chest, accompanied with his shrieks of terror.

And finally, there’s the lengthy conclusion which feels at times a bit too anticlimactic. While police psychiatrist Dr. Richmond insists he is giving the straight story concerning what took place at the Bates Motel (in regards to the deaths of Marion, the detective, and the other missing women), from a modern perspective of the justice system this feels awfully like an insanity plea. In what is arguably the most deeply disturbing scene in motion-picture history, ‘mother’ is conversing with herself inside Norman’s head. Norman Bates no longer exists, only his mother, Norma, does. A fly lands on his/her hand but to prove her innocence she chooses to spare its life. Not because he/she has turned over a new leaf but because the police are monitoring his/her every move and he/she wants to prove them wrong. “I'm not even gonna swat that fly” he/she says, “I hope they are watching. They'll see. They'll see and they'll know and they'll say, 'Why, she wouldn't even harm a fly.'” The film concludes with an excruciatingly chilling scene, a devilishly smiling Norman Bates with an image of mother’s grinning skull superimposed over him.

Sure, today Psycho is considered a revered classic, blasphemy upon anyone, whether it be Steven Spielberg or some unknown director, who so much as trifles with it. This is why the Gus Van Sant remake was dead upon arrival. The original however was loathed by film critics who now regard it as a cinematic masterpiece. Hypocritical on their part for sure but only over time do the ‘Hitchcockian’ charms of the famous director’s films grow on you as a viewer. True, John Gavin is a stiff as Marion’s boyfriend, Sam (Universal forced him upon Hitchcock’s picture because he was under contract with the studio), and Vera Miles could breathe more life into Marion’s sister Lila, but on the whole it has all the mannerisms and charm that made Hitchcock one of the greatest filmmakers in motion picture history. Nothing he does seems out of place or out of character with what audiences have been accustomed to expect from him.

My Rating: **** ½ out of 5 (Grade: A)

<< Home