Film Review - The 39 Steps

British film director Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps is a significant piece of cinema history for several reasons. It is generally considered to be his first spy-chase suspense-thriller, a genre he would return to, successfully, time and again throughout his motion picture career, most notably with Carey Grant in North by Northwest. More importantly however it was his first movie to find success among American audiences. More importantly however The 39 Steps would be his first movie to find success among American audiences. Few of his earlier black-and-white silent features made their way to American movie theatres and those that did, among them the sound-version of Blackmail, were dismal failures in terms of box office revenue. With the success of The 39 Steps he was at long last able to successfully make a name for himself in the United States. This in turn peeked the interest of studio executives searching for fresh talent and vision within the motion picture industry, although it would be several more years before he actually filmed his first American film. In part to this film he was able to achieve a level of success and acclaim he would never have been able to acquire simply a successful film director in England.

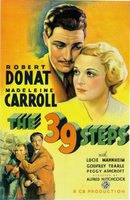

British film director Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps is a significant piece of cinema history for several reasons. It is generally considered to be his first spy-chase suspense-thriller, a genre he would return to, successfully, time and again throughout his motion picture career, most notably with Carey Grant in North by Northwest. More importantly however it was his first movie to find success among American audiences. More importantly however The 39 Steps would be his first movie to find success among American audiences. Few of his earlier black-and-white silent features made their way to American movie theatres and those that did, among them the sound-version of Blackmail, were dismal failures in terms of box office revenue. With the success of The 39 Steps he was at long last able to successfully make a name for himself in the United States. This in turn peeked the interest of studio executives searching for fresh talent and vision within the motion picture industry, although it would be several more years before he actually filmed his first American film. In part to this film he was able to achieve a level of success and acclaim he would never have been able to acquire simply a successful film director in England.Based on the novel of the same name by Scottish author John Buchanan, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1935 feature film adaptation bears little resemblance to its source. For one thing, the title, The Thirty-Nine Steps, is an allusion in the novel to physical steps along the coastline of Kent, England. In the film however they are instead used as a reference to the conspiratorial organization plotting an assassination attempts on a governmental official of a foreign nation. Another critical alteration from the novel is the character of Pamela who serves as a love interest to the hero of the picture, Robert Hannay. Pamela, or, more importantly, no love interest for that matter, exists in Buchanan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps. Her inclusion then significantly alters the theme of the story from an intense spy-thriller into a light-hearted yet still captivating romance. Literary purists will undoubtedly disapprove of such revisions but Hitchcock and playwright Charles Bennett actually strengthen Buchanan’s rather sluggish (at least as far as the middle section is concerned) novel. However, reaction may not have been as reputable as it was if it were not for the mesmerizing chemistry exuded between Robert Donat and Madeline Carroll. Audiences instantly notice a spark between the two from the moment they first encounter each other. In order to achieve such an effect, Hitchcock reportedly chose to film the handcuff scene first. After he had shackled the two together, he pretended to lose the keys which allowed the actors to feel each other emotionally and make their roles are the more believable and coherent.

The most striking transitional sequence in the film, arguably one of the more fascinating of his early career, is the scream of the chambermaid as she discovers the body of Annabelle in Hannay’s flat seamlessly transforming into the screeching whistle of a moving train. A brilliant example of director Alfred Hitchcock’s continuing apt experimentation with the blending of sounds and images. Such an effect would often be replicated throughout cinema history, most recently in director Steven Spielberg’s The Lost World in 1997.

A perpetual theme in The 39 Steps is the sexually-frustrating institution of marriage, a motif Hitchcock would return to on numerous occasions later in his career. Although this argument can be assigned toward all three examples in the film, including the ‘professor’ and his wife and the innkeepers, its authentication is shown through the shotgun marriage of Margaret and her abusive Calvinist crofter husband, John. Hannay and the audience take pity in the young girl who longs for freedom outside the shackled confinement of her maligning home. This can’t be exemplified any better then through her hanging onto every word Hannay speaks in regards to his journeys in London and Montreal. Both enjoy each other’s company, no more so then Margaret who is trapped in an unhappy marriage with no sign of escape. Her vehemence to help Hannay in his hour of need without so much as a question in regards to his true identity or his innocence in the crime he is implicated in demonstrates her thirst for company.

While Donat plays the character off mainly for laughs (the scene in which he quickly improvises a speech introducing a candidate for British Parliament, having no knowledge about either the candidate or the politics of Britain, is one of Donat’s more memorable moments in the film), he is easily able to slip in and out of reflective consciousness without offsetting the flow of the picture or the intensity of the drama which unfolds before our eyes as the story draws to a close.

It is a bit difficult today to take Lucie Mannheim’s Miss Annabelle Smith seriously, partly because of her heavy foreign accent, a cliché which has become a staple of parodies of spy films. Nonetheless, interactive dialogue between her and Robert Hannay and the character’s own mannerisms are pure Hitchcock spy-thriller material. In the aftermath of the mass confusion at the music hall, she begs Hannay to accompany him to his bachelor flat apartment. Slyly, almost prophetic really, he responds, “It’s your funeral”. Dark Hitchcockian humor at its best. In yet another example of Hitchcock cruel irony, the scene in which Smith collapses on Hannay’s bed as he lay in it with a knife stabbed in her back shows that she was killed with the same kitchen knife Hannay used to cut her last meal just a few short hours ago.

The scene in which Richard Hannay remembers the tune which had been stuck in his head for the past two days (this of course being the musical accompaniment for Mr. Memory’s act) is one of brilliant craftsmanship on the part of the director Alfred Hitchcock. The composition reveals that there were no papers missing from the Air Ministry in regards to their top secret weapon because Mr. Memory, an agent of the 39 Steps, memorized every single word of the document and kept the valuable information inside his head, leaving no incriminating evidence which would point toward him or the secret organization he worked for. It was almost the perfect crime. Sadly, Mr. Memory, a man ‘doomed by his own sense of duty’ as the famous director himself once put it, can not help but uphold his reputation as a cistern of information, whether it be trivial or valued. So when Hannay, being dragged from the theatre by the police who have finally caught up with him after his escape from the police station, shouts, “What are the Thirty-Nine Steps? Come on! Answer up! What are the Thirty-Nine Steps?” he hesitantly but accurately answers the question, or at least he tries to before the ‘professor’ who had been lying in wait in the balcony to take Mr. Memory to the home base of the secret organization shoots him and attempts to flee the scene before being cornered by the police. As Mr. Memory lays dying on the floor, having just gotten the secret information he ‘stole’ from the Air Ministry off his mind at long last, in the foreground Hannay and Pamela hold hands, this time voluntarily (laughably as the handcuffs still tangle from Hannay’s wrist), as in the background chorus-line dancers kick to the tune of ‘Tinkle, Tinkle, Tinkle’ on the air. Easily one of the director’s most captivating and elaborately complex scenes in his distinguished career.

Alfred Hitchcock’s masterful adaptation of John Buchanan’s The 39 Steps truly stands the test of time as one of the director’s most stimulating spy-thrillers from his early film career in spite of its numerous imitators over the decades.

My Rating: **** ½ out 5 (Grade: A)

<< Home